As the 1990s dawned, the status quo of the Nixon years had returned to Washington. A Democratic controlled Congress had recovered from the 1981-86 Republican Senate interregnum. The Republicans had become more conservative and more Southern, and the Bush 41 Administration's legislative hoped depended on a "conservative coalition" of the GOP and Southern moderate Democrats. There were stil quite a few; the old-school segregationists had died off but there were new-school military hawks like Ernest Hollings, Sam Nunn, and Al Gore Jr., who helped Bush start the first war against Saddam Hussein. Bush also saw victory in the high-profile Supreme Court battle over Clarence Thomas.

But the deck was about to shuffle wildly in 1992 and 1994. The next key phase of our transition to parliamentary style party discipline in Congress, defined ideologically, was the Gingrich Era.

But the deck was about to shuffle wildly in 1992 and 1994. The next key phase of our transition to parliamentary style party discipline in Congress, defined ideologically, was the Gingrich Era.I call the 1990s "the Gingrich Era" rather than "the Clinton era" deliberately. If anything, Clinton and Gore delayed the transition to a parliamentary-style disciplined party system by running explicitly against cutting "triangulation" deals with the Republican Congressional majorities on issues like welfare reform, and by focusing solely on the re-election race of 1996 and not down-ballot races.

While Clinton was a lonely leader, operating in detachment from his congressional party, Newt Gingrich was a classic parliamentary leader. He made his bones with the "special order" speeches of the 1980s, spouting conservative ideology and standing up to the Speaker Tip O'Neill, in "question time" fashion. He stage-managed the overthrow of O'Neill's successor, Jim Wright. Gingrich whipped his members into nearly unprecedented unanimous opposition to Clinton's 1993 tax bill. Most dramatically, he took the friends and neighbors politics of House elections and nationalized them, like you see in a parliamentary system, with the Contract With America.

Even Gingrich's departure from Congress, as the era climaxed with the Clinton impeachment, was in parliamentary style. After a disappointing 1998 election, when impeachment backfired as a campaign issue, Gingrich resigned. But by the time he left, the modern Congressional Republican Party, defiant and near-unanimous, had taken shape.

It took the Democrats longer. Clinton's conciliation set the stage for the timidity Congressional Democrats showed in the Bush 43 era. But the elections of 1992 and 1994 pushed the Democrats toward their own modern model.

1992 was a wacky election, full of primary defeats, scandals, and the on-again, off-again candidacy of Ross Perot. Perot's electoral impact was ephemeral, a one time tantrum that built nothing. Perhaps it was a catalyst in the throw-the-bums-out mood of 1994, but by 1996 it was little more than an ego trip.

Perot's support was strongest in the Mountain West, in two distinct kinds of places: depopulated ranch country and the newly settled, rootless suburbs around sprawltropolises like Phoenix and Vegas. But what's more interesting is that in the South and the cities, Perot totals were low. He had zero appeal to African Americans, and white Southerners were less likely to reject Bush 41 than the rest of the country.

Clinton carried scattered Southern and border states in his two runs, usually with under 50 percent, on a combination of near-unanimous black support and a slightly higher than average white vote. This was a brake on the realignment to ideological parties, as Democrats misread the numbers and fretted about alienating the white South.

As we saw during the 2008 Democratic primaries, a Clinton Democratic coalition is rather different than an Obama Democratic coalition. And there was movement toward our modern Democratic Party structure in 1992--but the important part was down the ballot.

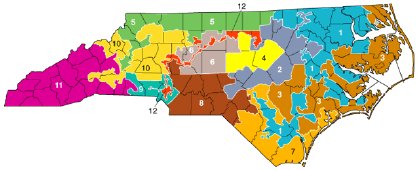

1980s court rulings required the creation of majority-minority districts wherever possible, and computerized matting technology had made gerrymandering easier. Eight southern states created new first black majority districts, and sent new black representatives to Congress--the first since Reconstruction in most states. The districts were works of modern art -- the "Melting Z" for Cleo Fields of Louisiana, the "I-85" North Carolina district of Mel Watt (connecting the black neighborhoods of several metro areas by a corridor that got as narrow as a median strip), and the "squashed headphone" district in Chicago, which connected two Hispanic areas by a strip of parks and cemeteries.

1980s court rulings required the creation of majority-minority districts wherever possible, and computerized matting technology had made gerrymandering easier. Eight southern states created new first black majority districts, and sent new black representatives to Congress--the first since Reconstruction in most states. The districts were works of modern art -- the "Melting Z" for Cleo Fields of Louisiana, the "I-85" North Carolina district of Mel Watt (connecting the black neighborhoods of several metro areas by a corridor that got as narrow as a median strip), and the "squashed headphone" district in Chicago, which connected two Hispanic areas by a strip of parks and cemeteries.But by packing minority voters into extreme gerrymandered districts, there was a tradeoff. Often, two moderate Democrats were replaced by a liberal black Democrat and a very conservative Republican. Ben Erdreich of Alabama, Jerry Huckaby of Louisiana, Tom McMillen of Maryland, Liz Patterson of South Carolina, and Richard Ray of Georgia all lost to Republicans, as new African American Democrats were winning one district over. And the moderate white Democrats who held on in `92 were swept out in `94, two each in Georgia and North Carolina.

This change in districting law meant more members who were not responsive to the needs and arguments of the other side. Another consequence was a House Democratic Caucus that was blacker, more Hispanic, and by coincidence more female, than any before. And not by coincidence, more liberal than any before.

The trend accelerated in 1994 when Democratic ranks were decimated. It was the moderates in swing districts, not the liberals in safe seats, who lost. The result was a remnant that was more ideologically consistent--the same thing we see in the Republican Caucus today.

1992 and 1994 also saw an unusually high number of retirements concentrated in the South. These were spurred both by a change in campaign finance law (and by reading the writing on the wall). Congressional ethics rules had changed and a big group of senior members retired just in time to pocket their campaign treasuries. Some of the last senior Southern Democrats left; the archetype was 53-year member Jamie Whitten of Mississippi.

A retirement on the GOP side was especially key: House Minority Leader Bob Michel, one of the last of the go along to get along school. In the House, he was succeeded by longtime aide Ray LaHood (now in the Obama cabinet), and in the leadership he was replaced by Gingrich. It's likely that had Bob Michel stayed on one more term, he would not have been Speaker; he would have been Minority leader again because the the landslide of 1994 might not have happened.

The unprecedented levels of retirements, redisticting and defeats meant that in January 1995, as Gingrich took the gavel, about a third of the members were in their first or second terms. The House was now dominated numerically by the Democrats of 1992 and their polar opposites, the Republicans of `94.

After these two wild elections, things settled back into stalemate. Some of the wins in both 1992 and 1994 had been flukes, but the long-term survival rate was far higher than the Senate class of 1980. Both sides had the power to block each other; neither could win alone. The modern congressional Republican Party was firmly in place, and the outlines of the modern Democratic Party were visible.

No comments:

Post a Comment