In the wake of the partisan passage of President Obama's stimulus bill, many electrons and dead trees have been devoted to Obama's "failure" to win bipartisan approval. Most of this has focused on short-term Republican strategy.

But I think something bigger is at work here. What we've seen this month is the fourth, and final, stage of a decades-long shift in the American party system toward the model that the rest of the world has: political parties centered around consistent ideology.

For decades, divisions in Congress were dominated by a "conservative coalition" of Republicans and Southern Democrats. That day is done. voting Sure, we still have Blue Dogs, but only seven that voted no on final passage (the eighth, Pete DeFazio of Oregon, opposed the bill from the left). Near-unanimous Democratic support was met with unanimous Republican opposition. It's an ideological consistency and level of party discipline never before seen in American politics.

It's been a staggered but steady trend, with roots dating back nearly a century and four distinct modern phases.

1964-72: The backlash era

1978-84: The Reagan era

1994-2004: The Gingrich-Bush era

2006-08: The Obama era

What's important is not so much the overall numbers as the regional and ideological sub-trends of conservatives toward the GOP and, more often ignored, liberals toward the Democrats.

This week, I'll look at these eras in a way too long multi-part series. Today, we start with the pre-history, and why our split into ideological parties didn't happen sooner.

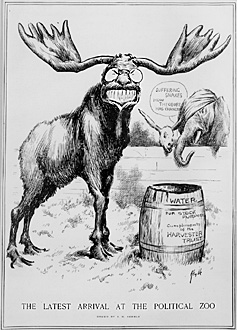

It almost did. The Progressives left the Republicans in both 1912 and 1924, and in an alternate history one of those splits could have realigned the system. But those candidacies were driven as much by personality as ideology, and the deaths of Teddy Roosevelt and Fightin' Bob LaFollette made the first two Progressive Parties dead ends. Republicans also learned their lesson from the divide-and-conquer politics of the 1912 Roosevelt-Taft split, when Democrats made big House gains and took control of the Senate while Wilson was winning with only 41% of the vote.

It almost did. The Progressives left the Republicans in both 1912 and 1924, and in an alternate history one of those splits could have realigned the system. But those candidacies were driven as much by personality as ideology, and the deaths of Teddy Roosevelt and Fightin' Bob LaFollette made the first two Progressive Parties dead ends. Republicans also learned their lesson from the divide-and-conquer politics of the 1912 Roosevelt-Taft split, when Democrats made big House gains and took control of the Senate while Wilson was winning with only 41% of the vote.So the progressives delayed America's split into ideological parties for nearly a century, and returned to the Republican Party, where the great battles of the late teens and twenties were fought out. The conservative Taft-Harding-Coolidge-Hoover-Taft wing prevailed over Teddy Roosevelt, Fighting Bob LaFollette, and the Non-Partisan League of the Dakotas (which fought its electoral battles in GOP primaries, primaries themselves being a Progressive Era reform).

The Democrats were reduced to a regional party: the Solid South, voting as they shot in the Civil War, and a handful of northern urban ethnic machines (some but not all; the machine politics of Pennsylvania were Republican, which is why the Keystone State held for Hoover in 1932).

Machine politics, be it Boss Tweed in the North or Boss Hogg in the South, are essentially conservative: buy in and keep the establishment in power, in exchange for some petty patronage. Wilson, the lone Democratic president of the 1896-1932 Progressive Era party alignment, was deeply conservative on matters of race and dissent.

The New Deal coalition relied in part on these machines north and south, but put the internal contradictions of the Democratic Party into sharp and uncomfortable relief. A thin common thread of economic interventionism, and the force of FDR's personality, held them together. Roosevelt himself saw those internal contradictions and tried unsuccessfully to goose the Democrats left in the "primary purges" of 1938 (another historic turning point when we could have seen modern ideological parties).

The internal strain grew as northern blacks, their numbers swollen to electoral significance by migration from the South, left the Party of Lincoln. The milestone here is 1934 when Republican Oscar DePriest of Chicago, the lone black congressman, lost to Arthur Mitchell, the first black Democrat in Congress. But in the South, the tiny fraction of enfranchised blacks stayed Republican, in opposition to the segregationist Democratic establishment. Rev. Martin Luther King Sr. remained a Republican until 1960.

The Republicans were now the ones shrunk to a regional rump party. They lost the House in 1930, when a handful of progressives (in one of their last hurrahs) voted with Democrats on organization (much like the recent coup in the Tennessee House where Democrats elected got one moderate Republican to defect). The Republicans lost seats four cycles in a row and were down to only 88 House seats in 1936. The dominant wing was rock-ribbed rural Midwesterners, as epitomized by Alf Landon, against intervention both foreign and domestic. But there was a smaller yet still significant Northeastern wing: good-government moderates put off by the New Deal's price tag and genuinely offended by segregation.

The handful of remaining Roosevelt 26 era rural progressives, like George Norris of Nebraska (who abandoned the GOP label and won as an independent in `36) and Bill Langer of North Dakota, faded away with the years, The LaFollettes experimented with a Wisconsin Progressive Party, as did Minnesota with the Farmer-Labor Party. These one-state movements weren't tied too much to the 1948 Progressive Party of Henry Wallace (a registered Republican until nominated for Vice President in 1940), though there was at least one connection to the Dakota tradition: a young George McGovern backed Wallace over Harry Truman.

By 1946 Farmer-Labor had merged with the Democrats, an early watershed in the move to national ideological parties. The Minnesota DFL has played an outsized role on the national stage: Hubert Humphrey, Gene McCarthy, Walter Mondale, and Paul Wellstone. But in Wisconsin the Progressives unsuccessfully re-joined the GOP, and there was another watershed: Robert LaFollete Jr.'s primary loss to Joe McCarthy, the spiritual godfather of Lee Atwater and Karl Rove.

Humphrey helped bring about the first big revolt of Southern segregationists at the 1948 Democratic convention, as his civil rights plank led to Strom Thurmond's candidacy (a precursor to the next chapter in our story). But the Dixiecrats weren't the first Southern electoral revolt. An anti-New Deal slate of "Texas Regulars" pulled nearly 12 percent of that state's presidential vote in 1944.

Humphrey helped bring about the first big revolt of Southern segregationists at the 1948 Democratic convention, as his civil rights plank led to Strom Thurmond's candidacy (a precursor to the next chapter in our story). But the Dixiecrats weren't the first Southern electoral revolt. An anti-New Deal slate of "Texas Regulars" pulled nearly 12 percent of that state's presidential vote in 1944.While there weren't many rural-style progressives left in the Republican Party after the New Deal, there were still a lot of urban moderates and liberals, and their numbers grew as the GOP recovered from the near-knockout punches of the 1930-36 elections. This wing prevailed, for the last time, in 1952 when Eisenhower defeated Robert Taft for the GOP nomination (while Adlai Stevenson appeased the South by naming Alabama's John Sparkman as his running mate). The Republicans made some presidential inroads into the outer South in 1952 and 1956, but that was more about Eisenhower than party.

So that gets us to the end of our set-up chapter, in 1952. We had two parties defined as much by region as ideology. While agrarian progressives had mostly moved toward the Democratic Party, there were still liberals, moderates, and conservatives in both parties. The party label you chose had as much to do with the traditions of your state as with your ideology. It was the age of bipartisanship that the David Broders of the world pine for, an Era of Good Feeling where Sam Rayburn, Lyndon Johnson, Joe Martin and Ev Dirksen would gather for drinks and cut the deals. As long as no one touched the third rail of race, everybody got along.

But that third rail was electrified in 1954 with the Brown decision. In Part Two I'll look at the electoral trends of the civil rights era, the real beginnings of our modern partisan era.

No comments:

Post a Comment