Lyndon Johnson famously said that he'd signed the South away from the Democrats for a generation when he signed the Civil Rights act, and he was about right. The civil rights legislation of the mid-1960s was both the high water mark and the beginning of the end for bipartisanship. The coalition of liberal Democrats and moderate Republicans overcame the Solid South in Congress, but in doing so, it shook the Southern electorate loose from its partisan moorings.

But we were still a generation away from the full realignment that solidified last week with the unanimous zero on the stimulus bill: an America with two parties fully distinguished by ideology without overlap.

A look at Southern election results from the 1960s shows nothing short of a revolution: bizarro world swings, depending on whether the white South was using a third party strategy or backing the GOP that year. Look at Mississippi: 58% Democratic and 17% Unpledged in 1956, 39% Unpledged in 1960, 87% Republican in 1964, 65% Wallace and 14% Republican 1968, 78% Republican 1972.

1964 was the turning point. And the most important thing that happened in terms of long-term realignment that year wasn't that Barry Goldwater was nominated. That wasn't even second place. The second most important thing was that the Goldwater convention booed Northeastern moderates William Scranton and Nelson Rockefeller, their first explicit rejection of the old liberal tradition.

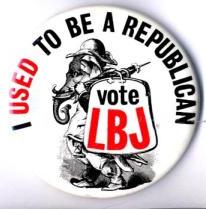

The most important thing that happened in 1964 was that Strom Thurmond endorsed Goldwater. (That or the Beatles.) Thurmond was the first big-name Southerner to not just bolt from the Democrats (he'd done that once before), but to go so far as to join the Republican Party. It was a tough move for Southern whites, who grew up on stories from Confederate grandfathers. Even 100 years after the War Between The States, Republican was still a cuss word.

The first electoral moves after the Brown decision of 1954 were tentative and ad-hoc, against the national Democratic Party but not yet toward the Republicans, like segregationist Dale Alford's 1958 write-in House win in Arkansas and the unpledged Democratic electors of Alabama and Mississippi in 1960. There was almost a downballot Republican breakthrough with a near-win in the 1962 Alabama Senate race.

Segregation was a winning issue for Orval Faubus and George Wallace in a still all-white electorate, and Wallace expanded that into the 1964 Democratic presidential primaries where he rolled up a significant protest vote, even in border and Northern states. But all of those were within, rather than away from, the Democratic Party.

Texas, where the Republican Great Plains met the Democratic South, was almost ready to embrace the Republican Party, voting twice for Eisenhower and barely for Kennedy-Johnson. They broke through in 1961, electing Republican John Tower to LBJ's Senate seat. But suddenly, one day in Dallas, Johnson was president, and the home state presidency stalled those GOP gains for a few years.

But in the Deep South, without Texan pride, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was the last straw. Goldwater rejected the Civil Rights Act of 1964 out of small government libertarianism rather than racism, but to the deep South, no was no and they embraced him.

The 1964 landslide was really two separate elections: a Johnson landslide in the Union and a Goldwater landslide in the Confederacy. It was only close in a handful of border and Western states. Goldwater swept in five House Republicans from Alabama, one from Georgia, and the only one who ran in Mississippi. (Few of them lasted; several of them overplayed their hands and ran unsuccessfully for higher office a little too soon in 1966.)

The 1964 landslide was really two separate elections: a Johnson landslide in the Union and a Goldwater landslide in the Confederacy. It was only close in a handful of border and Western states. Goldwater swept in five House Republicans from Alabama, one from Georgia, and the only one who ran in Mississippi. (Few of them lasted; several of them overplayed their hands and ran unsuccessfully for higher office a little too soon in 1966.)But the bigger milestone than that handful of Goldwater newcomers was before the election, when Thurmond joined the GOP. There was another minor aftershock in South Carolina; Rep. Al Watson was booted from the Democratic Caucus for endorsing Goldwater, resigned, and won the special election as a Republican.

Ole Strom made it OK for a redneck to be a Republican. And in the end it's the Thurmond tradition, dominated by stirring the hate pot of social wedge issues and racial code, that's more important than Goldwater's Wild West small government libertarianism. ("You don't have to be straight, just shoot straight," Goldwater said of gays in the military late in his life.)

At the same time, newly enfranchised African Americans were moving more solidly to the Democratic Party. It wasn't always successful, as Fannie Lou Hamer and the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party found out (there was also a black National Democratic Party of Alabama). Bt in the end blacks opted to overcome segregation within the Democratic Party, where at least nationally they seemed welcome. Nationally, black voters had been about two to one Democratic in the pre-Goldwater era, but now those numbers jumped to the 85% range. And in a conundrum we still see today, the higher the black percentage of the electorate, the higher the percentage of white vote goes Republican.

The 1965-66 Great Society Congress had an overwhelming Democratic majority, but the Democrats didn't consolidate on ideology. There were still some old-time Southern conservatives like Herman Talmadge, John McClellan, and James Eastland to contend with, and the divisions of the Vietnam War were soon to surface.

As the national party moved left, at least on social and economic issues if not in peace, in the `60s, the southern Democratic bulwark that was Virginia crumbled. Conservatives Senator Willis Robertson (Pat Robertson's father) and House Rules Chairman Howard Smith lost their primaries; Smith's seat went Republican. Republicans won the governorship in 1969, and by 1970 Harry Byrd Jr., the scion of the old party machine, was so pessimistic about his chances in a primary that he ran as an independent. In 1973 former Democratic governor Mills Godwin made a comeback as a Republican.

Other breakthrough electoral victories popped up in the South: Howard Baker in `66 and Bill Brock (who beat Al Gore Sr.) in 1970 in Tennessee, Ed Gurney in Florida. More and more, new conservatives in office were Republicans. There were still some occasional arch-conservative Democratic newcomers, like Louisiana Rep. John Rarick, but most of the new generation of Southern Democrats were moderates like Reubin Askew of Florida, Terry Sanford of North Carolina, and Jimmy Carter of Georgia. And most new conservatives, like Lott and Gurney, are Republicans.

Nixon led the late `60s transition from flagrant race baiting to code words and issues: law and order, welfare, busing, "values" issues. In 1972 he ran more against George McGovern's supporters ("aacid, amnesty, abortion") than he did against McGovern, a war hero who got swift boated three decades before we heard the term. Democrats grappled with the symbols left over from the McGovern campaign, and the Battle of Grant Park at the 1968 convention, for 36 years. Now, McGovern's national percentages in 1972 were only about five points below Hubert Humphrey's in 1968, but in a two-way race rather than a three-way it was devastating. Yet it was a lonely landslide for Nixon as the government stayed divided.

In Texas, with Johnson now gone, outgoing Gov. John Connally first joined the Nixon cabinet and then the Republican Party itself. Other than Thurmond, the high-seniority DC delegations of the South played out the string as Democrats. Southerners got more and more used to splitting their tickets: Republican for president and then Democratic for good ole Congressman Bollweevil. But the GOP's success gradually trickled down and there were some Southern firsts, usually when Ole Bollweevil retired. Trent Lott went to the House with his Democratic predecessor's endorsement, the Republicans finally took that Virginia Senate seat, and Jesse Helms, who plays so big a role in the next chapter, won the 1972 North Carolina Senate race.

In the other direction, handfuls of northerners were shifting to the Democrats, like Congressman (later Senator) Don Riegle in Michigan. New York Mayor John Lindsay lost his 1969 Republican primary, was re-elected on the Liberal ticket, and eventual ran for president as a Democrat (very badly). Yet there was still a strong centrist element in the GOP. Great moderate hope Charles Percy failed in his bid for Illinois governor in 1964, but made it to the Senate two years later.

Divided government now became the norm for the first time in American history. From 1968 to 2002, only 6 1/2 years (Carter, first two years of Clinton, first six months of W) saw a President and both houses of Congress under one-party control.

So by 1972, the elements of the modern system are in place. Led by Thurmond and Nixon, white Southerners have largely migrated to the Republican Party at the top of the ballot, and are beginning to consider some down-ballot Republicans. The move to ideologically defined parties seems to be underway, awaiting only the generational attrition of senior Democrats.

But for today, our story ends with Watergate. The first beneficiary of the Southern Strategy was flushed from office, the Democrats made huge Congressional gains in 1974, and Jimmy Carter swept in on a reform wave in 1976. For a moment, it seemed Carter had re-created the FDR coalition. It was a brief and misleading moment.

No comments:

Post a Comment