While I was never going to be satisfied with the Iowa Democratic

Party’s first effort at a party-run primary (“mail-in caucus” in IDP’s

language), which wrapped up March 5 with a results announcement, there were at least some successes.

In fairness, with Iowa Republicans still First In The Nation on their

side and opposed to any substantive changes to accommodate the new

calendar that removed Iowa from the early Democratic states, IDP didn’t

have many realistic options other than what they did: a January 15

in-person caucus for party business only to comply with state law, and a

later mail-in process to comply with Democratic National Committee

rules.

I recommended that plan myself long before IDP implemented it.

For the first time in three cycles, the IDP produced results promptly

and without controversy, though the format was sub-optimal and did not

include the all-important percentages used to calculate delegate counts.

(At this writing it appears non-Biden groups are not viable anywhere,

and late arriving ballots in the next few days are unlikely to change

that.)

The turnout of 12,193 as of March 6, while low, is in the same

general ballpark as the in-person attendance during Barack Obama’s 2012

re-election year caucus. And we got about one hour of media attention at

the beginning of Super Tuesday coverage, before polls closed in states

that were voting in person.

So as a dry run in a more or less uncontested year, not bad. NASA

didn’t land their first rocket on the moon either—they had to get John

Glenn into orbit first. But as a critic, and as someone who’s worked on a

lot of caucuses and elections, I’m focused on the Room For Improvement

side of the ledger. What did we learn and how can we make it better?

First and most importantly:

We should have accepted long ago that our role as an early state is over.

I would have felt better about all this had IDP leadership

immediately accepted the reality that Iowa is no longer an early state,

and started working toward both a post-First era of party building and a

presidential primary run by county auditors.

IDP chair Rita Hart is in a bind between rank and file activists like

me who care more about HOW Iowa votes than WHEN we vote, and old guard

stalwarts who think Iowa should have defied the Democratic National

Committee the way New Hampshire did and held an old fashioned Stand In

The Corner To Vote caucus on January 15 anyway.

But a system that required in person attendance at a long meeting was

indefensible in the party of voting rights, and the summer 2022

proposal to change to the mail-in system was too little too late for a

DNC that was already hostile to Iowa’s demographics and past errors.

Iowa Democrats should have thrown in the towel in December 2022, the

moment President Joe Biden named five other states as the early states

and said caucuses should no longer be part of the Democratic Party’s

nominating process. State Representative Ross Wilburn, then near the end

of his term as IDP chair, should have loudly and publicly said “it’s

over,” loudly and privately told the Des Moines donor class the same,

and introduced a presidential primary bill on Day One of the 2023

session, with every legislative Democrat as a co-sponsor.

Instead, under both Wilburn and Hart, we had ten months of secrecy and denial—almost

certainly because of back stage maneuvering to try to squeeze into the

early states after Georgia Democrats took themselves out of the running

due to lack of cooperation from Georgia Republicans. And once IDP

leaders finally accepted being out of the early states for 2024 as a

fait accompli, everything about the way they “accepted” it indicated

that they still consider it just a temporary setback and that they

intend to get early state status back in 2028.

Iowa cannot change its old and white demographics, and that alone may

be too much to ever overcome in a party that values diversity. But we

can try to change our process and our electoral results. We do not even

deserve to be considered as an early state till we have an auditor-run

primary and until we win some elections. Those items, rather than a

futile fight for First, should be our priorities.

While we eventually complied with the rules, we should have done so much sooner. The Biden campaign suffered as a result.

The DNC has strict rules about campaigning in states that are not in

compliance with the nomination calendar. That’s why, when New Hampshire

refused to go along with its assigned date, Biden had to run there as a

write-in candidate. He made the new rules, and he followed them. Iowa’s

“contest date”—the results release on Tuesday—was not in compliance with

the DNC rules until October.

Biden was never going to campaign here the way he did as a

non-incumbent—but the strict rules mean even surrogates and local

volunteers had their hands tied. Last summer, while a score of

Republican candidates barnstormed the state, and while rogue Democrats

Marianne Williamson and Dean Phillips stood on the State Fair Soapbox,

local party activists could barely utter the name “Biden.” We had to

worry about whether carrying a Biden sign in a parade would get the

president in trouble with his own rules.

Biden’s critics had the state to themselves for months, and the president’s campaign can’t get those months back.

New Hampshire needs to be thrown out of the national convention.

For a couple of ridiculous weeks, DNC chair Jaime Harrison insisted

on calling his native South Carolina “First In The Nation,” emphasizing

their newly assigned slot on the calendar even after New Hampshire had

voted. I get that South Carolina was excited about their new role. But

they very objectively were not First. New Hampshire was.

New Hampshire was encouraged, even begged, to do more or less what we

did—make the state run primary a non-binding “beauty contest” to comply

with state law in a Republican controlled state, and hold a party-run

process later to allocate national delegates to comply with the DNC

calendar.

They refused. They don’t care about a 50 percent reduction in

delegates, and they don’t care about Biden staying off the ballot. They

care about voting First, and they won the only battle they cared about.

The national press played along with countless “Biden is in trouble in

New Hampshire” reports (he won with 64 percent as a write-in).

We did it way too late, with way too much reluctance, and we are

still in denial, but in the end Iowa did follow the DNC rules. New

Hampshire did not. South Carolina leaders were conciliatory after their

voting date, arguing that New Hampshire should be seated at the

convention. I’m less generous. Our state got punished pretty

significantly for the results failure of 2020, which was unintentional

(the finger pointing over Who Broke The App will never end). New

Hampshire broke the rules on purpose.

The DNC will never be able to set state law, but they need to set an

example to discourage other states, and the only way to set that example

is to completely bar New Hampshire from the convention. Ooh, but what

if it costs us the state in November? Only the 20 party bigwigs who

would have been delegates will care, and they’re the exact people who

need the lesson.

The IDP still owes us some explanations.

Why did Iowa Democrats stall on setting our contest date from December 2022 until October 2023? I know the answer—we were lobbying for the Georgia slot—but someone needs to be honest about that.

How much was spent on the outside consultants who managed the vote,

when we have 99 auditors who know how to count? Every dollar spent on

this party-run primary is a dollar that won’t be spent on a tough

legislative race.

It would have been a worst-case option, but given the shaky state of

IDP finances, and the relatively low turnout, it might have been

reasonable to forego a vote entirely and just have had the state central

committee select a delegate slate. Yes, that’s an insider process, but

so is a party-run primary that only a little bit bigger circle of

insiders know about.

Why were the first ballots sent out more than two weeks after the announced January 12 date?

How were requests managed to make sure that voters did not attend

Republican caucuses on January 15, change party again before the

February 19 deadline, and request a Democratic ballot? There was a lot

of emphasis that this was illegal, but only vague explanations of what would be done to prevent it.

(The only fail-safe ways would be to share valuable and proprietary

caucus attendance lists with the Republicans, which is unlikely—or to

have a government-run primary.)

What about claims from multiple

voters that they never received their ballots? That may have been user

error with the online request process—but why was there no system for

voters to confirm that requests had been accepted and that ballots had

been sent or received?

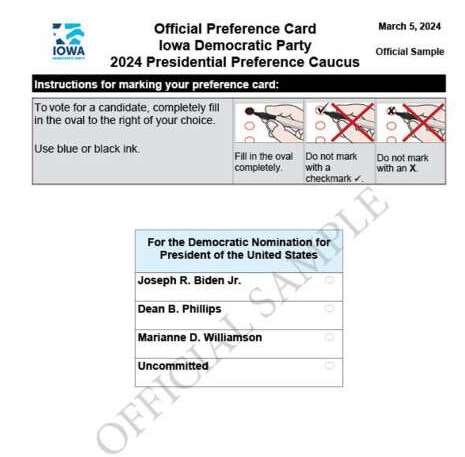

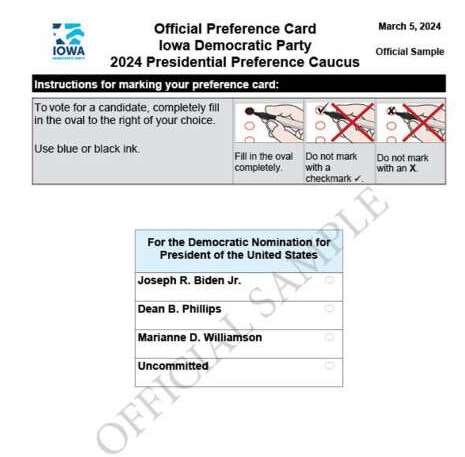

The language was part of the problem.

Why did the terms “preference card” and “mail-in caucus” annoy me so much? Because the language is part of the denial.

After the 2016 de facto dead heat in Iowa, the DNC adopted a rule

saying caucus states had to include a recountable document – since you

can’t re-count the heads when they are no longer in the room.

In discussions with New Hampshire, IDP learned that the word

“ballot,” and especially the process of qualifying for a ballot, were

key elements of what the New Hampshire Secretary of state considered the

difference between a “caucus” and an “election.” So IDP came up with

the term “presidential preference card” (NOT a “ballot”) and made them

all write-in (thus there was no process to qualify).

In this cycle, with Iowa Democrats officially scheduled after New

Hampshire, we should no longer care if the term “ballot” triggers them. A

little common-sense language would have gone a long way toward

convincing critics that IDP really is committed to a new post-First era.

Yet IDP insisted on calling something that any reasonable person

would call a “ballot” a “preference card” instead, and called their

mail-in voting process a “caucus.” That sent the message that they

consider 2024 a temporary setback and that the “natural order” will be

restored in 2028. At least this time they put candidates’ names on the

“preference cards.”

With few exceptions, state journalists uncritically parroted IDP’s

Newspeak terms “preference card” and “mail in caucus” in the few stories

that publicized the process.

Granted, process stories aren’t as fun as chasing candidates. The

state press and IDP could do little about the fact that Biden was not

going to actively campaign here. In 2012, Barack Obama wasn’t here much

either—but he had a large campaign presence in Iowa, which was still a

swing state. In 2024, Iowa is about electoral vote 420 on Biden’s depth

chart.

So there wasn’t much Democratic news to report. But the stories that

did run tended to be too late and too vague—“Deadline to request

preference card is today” was a typical story. Confused voters would

call their auditor the next day (as the deadline fell on President’s

Day) only to be told it was too late and there was no way to vote in

person. And when the “preference cards due today” stories landed,

auditor staffers like me had to field phone calls from voters standing

outside their polling places wondering why they weren’t open.

It didn’t help that there was publicity, including two tweets from

Vice President Kamala Harris’s account, listing Iowa as a Super Tuesday

state and urging people to go out and vote.

The party needs a better publicity plan.

This may be the most realistic place to expect improvement.

If we will be stuck with this hybrid process for the future, which

seems likely, Iowa Democrats need to find better ways to get the word

out and boost turnout. The public expectation—a mass mailing to all

registered Democrats—is too expensive for a financially challenged

party. But the online request process required voters to already be kind

of in the know about the inner workings of the party, and confused many

older voters. And, again, there was no confirmation email to indicate

the request had been successfully completed.

Maybe a contested nomination process will take care of the publicity.

We will never again see the kind of candidate resources we saw back in

the days of First, but even as a Super Tuesday state we’ll see more than

the nothing we saw this cycle.

Democratic legislators need to introduce a primary bill.

The lack of a primary bill makes it look like Iowa Democrats are more

committed to the donor class (who feel they have a constitutional right

to personal phone calls from presidential candidates) than to our role

as the party of voter rights.

We are past the “funnel” deadline for the 2024 legislative session,

but there is still time to offer amendments, and there are still

election bills pending. I know it won’t pass, and there are of course

many other priorities this session. Yet legislators had time this week

to introduce two dozen troll amendments to the Don’t Tread On Me license plate bill.

A primary bill is still valuable for the purposes of discussion, and

to show national critics that Iowa Democrats are committed to change.

The sooner the Iowa Democratic Party truly lets go of its early state

fantasies, the sooner we can start undoing the damage Republicans are

inflicting on our state.